Woodhall Park River Restoration (2020)

Figure 1: Woodhall Park and Broadwater - Courtesy of Affinity Water

The River Beane is a chalk stream that flows through the county of Hertfordshire and is 30.3km in length from its source at Roe Green. As a tributary of the River Lea, it rises to the south-west of Sandon, in the hills northeast of Stevenage, and joins the Lea at Hartham Common in Hertford. Chalk streams are fed by clear, alkaline chalk groundwater and springs making them very biologically diverse. There are only 200 chalk streams globally; most of these are found in Southern England making them important to protect.

Chalk streams

Chalk streams have been heavily modified through time for the purpose of industry and settlement. For example, stretches have been redirected around field boundaries to maximise field area for agriculture or to create mill leats for paper and flour mills. They have been dredged and widened to increase their capacity and controlled by weir and sluice structures for watercress beds, fisheries, and ornamental lakes.

Chalk streams should have a wide range of habitats including a variation in flow throughout the long and cross section, marginal and in channel vegetation, exposed gravel bed and an ephemeral head that wets and dries frequently depending on groundwater levels, predominantly led by the amount of rainfall. All these habitats should mean a vast range of macroinvertebrates from snails to shrimps and caddisfly, macrophytes such as water crowfoot and starwort, and fish species like brown trout and perch. As well as riparian species such as otter, water vole and kingfisher, all coexisting in a sustainable ecosystem.

The River Beane

The River Beane has been identified by the Environment Agency as failing to meet Good Ecological Status as defined by the Water Framework Directive. The river is failing for fish numbers and macroinvertebrates diversity. It has also been identified as being impacted by abstraction of groundwater for public drinking supply.

Under the National Environment Programme, Affinity Water were asked to carry out physical modifications of chalk steams in 7 catchments where abstraction for public water supply was deemed to be having a detrimental impact on their resilience to flood and drought conditions. The River Beane at Woodhall Park was identified as one of these river restoration projects.

Figure 2: Horseshoe Weir (2016) – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Woodhall Park

Woodhall Park (Figure 1) located in Watton-at-Stone near Stevenage forms the heart of the Woodhall Estate and is a Grade II listed parkland. The River Beane flows through the Estate over two significant weirs; the Tumbling Bay Weir which creates an ornamental waterfall and holds back an impressive broadwater, and the Horseshoe Weir 700m downstream of Tumbling Bay Weir which was installed for ornamental purposes.

In April 2016, a storm resulted in a breach of the broadwater bank, causing the lake to drain down. It was realised that over time the broadwater had filled with silt which was found to be contaminated with hydrocarbons so required remediation. The Estate wished to remove the silt and had it treated on site so it could be spread safely on their land.

Affinity Water took the opportunity whilst the lake was being repaired to improve the connectivity of the river by bypassing the two weirs. This was done in two phases; downstream first by bypassing the Horseshoe Weir with a 400m channel, and then the upstream section bypassing the broadwater and Tumbling Bay Weir with 900m of channel.

Phase 1

The Horseshoe Weir (Figure 2) was acting as a barrier to fish passage and impounded flow upstream of the structure. The section of river upstream of the weir was artificially straightened and had few natural chalk stream features. The weir is ornamental and has a Grade II listing which meant it could not be removed. In order to enable fish to migrate up and downstream (which is important for breeding and mobilising downstream during drought conditions) and to create a more naturally functioning chalk stream reach, it was decided that the weir needed to be circumvented by means of a bypass channel.

Aerial photographs showed that the field to the west of the channel, which was used for grazing cattle, was likely the original path of the River Beane. This can be seen in Figure 3 where the dark green vegetation shows a naturally wetter path and therefore the most likely historic route of the River Beane. The Woodhall Estate agreed that some of the grazing field could be used to reinstate the river channel back to its more natural location. This would mean the river would be better connected to the upstream section for fish movement by bypassing the Horseshoe Weir with the additional benefit of better groundwater connectivity and more natural chalk stream features.

Figure 3: Historic location of channel looking from North to South (October 2017) – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Phase 1: Design and construction

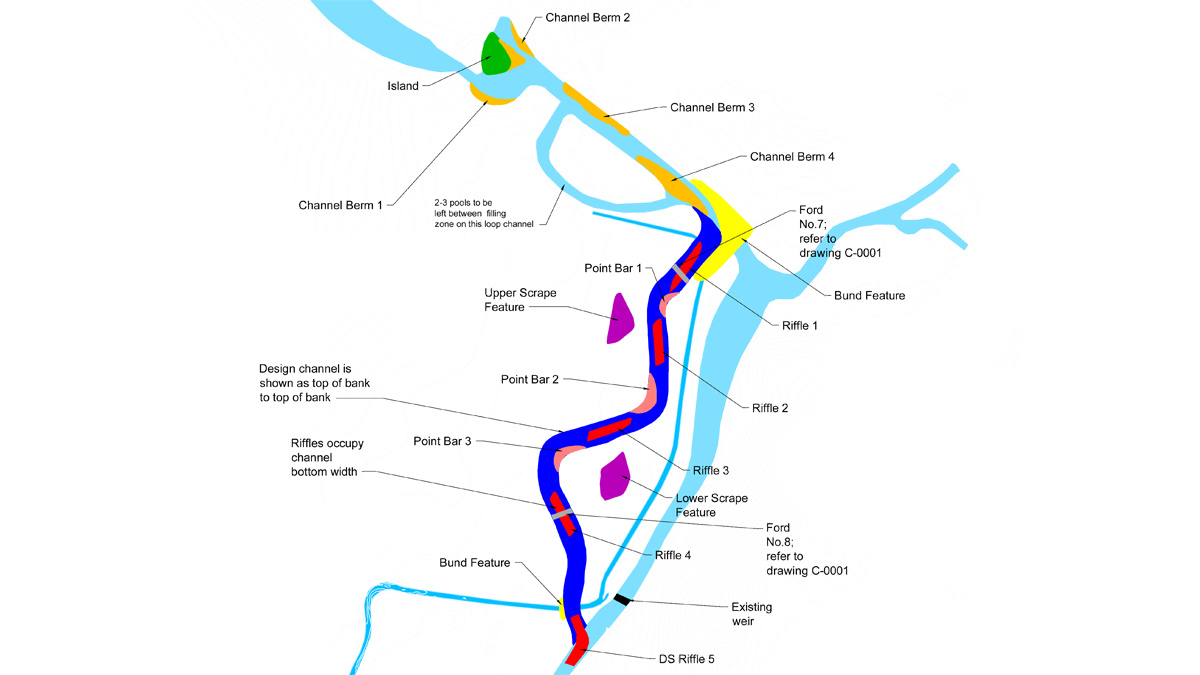

The design (Figure 4) was carried out by AECOM and was agreed with the Woodhall Estate, the Environment Agency (EA) and Natural England. Archaeologists were on site during excavation to ensure that nothing of historical importance was found on site, as the area is known for Roman remains. The design was run through the EA flood model to ensure that flood risk was not increased up or downstream of the project. Modelling was also carried out to calculate the correct bed elevation of the new channel, ensuring it would function hydrologically. Construction of Phase 1 was carried out by Salix River and Wetland Services, starting in October 2017 and was completed in January 2018.

Figure 4: Design for Woodhall Phase 1 – Courtesy of Affinity Water

The original channel has been left in situ as an offline pond behind the weir, which is fed by occasional flows from the Dane End tributary after heavy rainfall.

The bypass channel created 400m of new chalk stream habitat following construction. Riffles, pools and berms were created in the new channel to provide a range of habitats along this stretch. Local gravels were used to create the riffle features and create natural characteristics of a chalk stream. The Woodhall Estate have planted a number of trees on the right-hand side of the new channel to create an area of wet woodland. Fencing has also been installed so that the rest of the field can be grazed again, without the risk of poaching.

As part of the project, a volunteer day was held with Affinity Water staff, staff from the Woodhall Estate, and members of the River Beane Restoration Association to rescue aquatic and marginal plants from the drained down broadwater before the silt was removed from it. The plants were dug up and planted in pots in the summer of 2017 and kept in the offline section of the old channel over winter. In spring 2018 they were added to the berms by Woodhall Estate staff so that the new channel could vegetate over the summer with native species. Figure 6 shows the channel in summer 2019.

(left) Figure 5: New channel and offline pond behind Horseshoe Weir and (right) Figure 6: Phase 1 new channel (August 2019) – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Woodhall Park River Restoration: Supply chain key participants

- Principal contractor: Salix River and Wetland Services

- Designer: AECOM

- Designer: John Berry Associates

- Ecologist: Abrehart Ecology

- Ground investigation: Geotechnical Engineering Ltd

- Sub-contractor: Maydencroft

- Sub-contractor: Herts Renovation

Phase 2

Phase 2 of the project on the upstream reach at Woodhall Park began in September 2018 and consisted of the excavation of 900m of bypass channel, breaking off from the River Beane just north of the broadwater, and entering just downstream of the Tumbling Bay Weir in to Tumbling Bay. The objective of Phase 2 was to improve fish passage, create a range of chalk stream habitats, and to split the flow of the River Beane between the new channel and the existing broadwater. This enabled the lake feature to be retained as part of the parkland, but also allowed wildlife to flourish in a flowing river channel, creating multiple habitats.

Phase 2: Design and construction

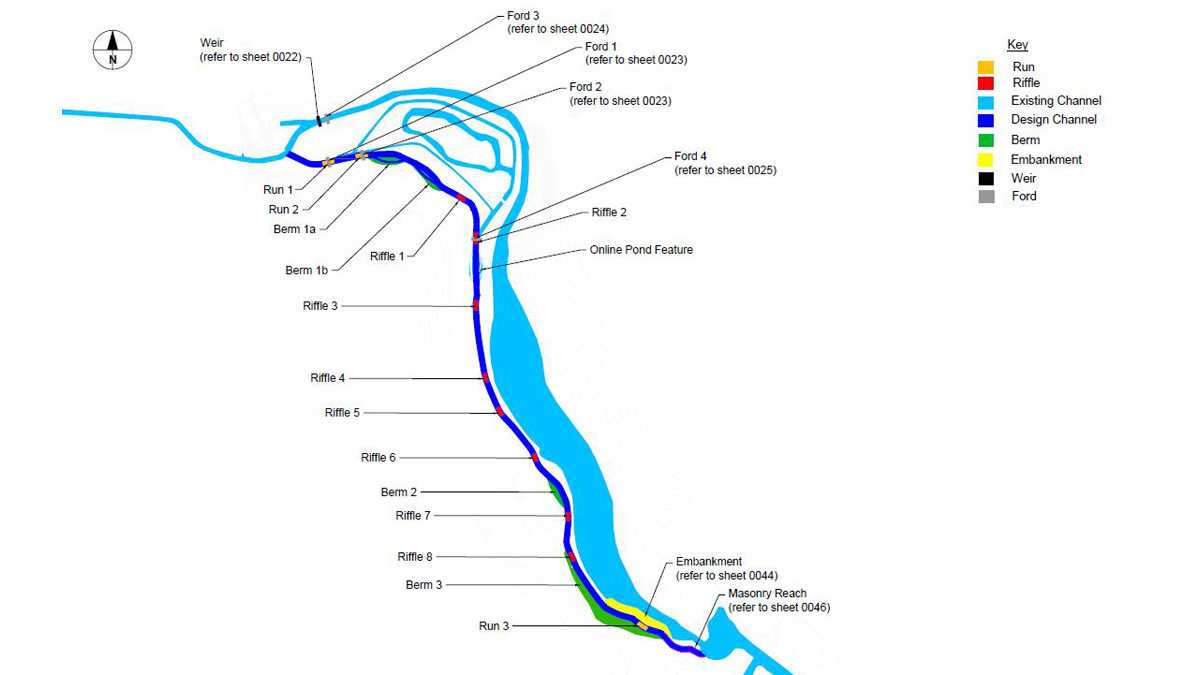

The design for Phase 2, carried out by AECOM can be seen in Figure 7. Unlike Phase 1, there were a number of design constraints in the Phase 2 location due to the presence of a large sewage trunk main to the west of the proposed channel, a number of veteran oak trees that Affinity Water wished to retain, and the existing driveway and access to the main Estate offices which restricted the width of the channel as it entered Tumbling Bay.

Figure 7: Design of Phase 2 – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Great crested newts were identified on the site and so special consideration was needed during the design and construction phases. A licence was obtained from Natural England and an ecologist from Abrehart Ecology was present during construction. Day and night searches were carried out as part of the licence and Affinity Water staff volunteered their time to assist the ecologist with night-time searches. As part of the licence, the Woodhall Estate are carrying out further improvement works around the great crested newt breeding ponds to improve the habitat.

Salix River and Wetland Services carried out the construction work as with Phase 1. The most downstream section of the Phase 2 channel, where it re-enters the Tumbling Bay, was constructed with vertical sides using sheet piles due to the lack of space. Due to the space constraints, a clay-core compacted embankment was constructed (shown yellow on Figure 7) which ‘pinched’ the Broadwater in, narrowing it as this point, and created the left bank of the channel.

(left) Figure 8: Piling rig creating vertical sided section and (right) Figure 9: Spider excavator creating a bund to allow for a dry bed in which to construct the clay embankment – Courtesy of Affinity Water

This whole reach has been gravel-lined and low planted berms have been created on alternating sides to meander the river through this straighter section which created a low flow channel, but still allows the water to inundate the berms in higher flows. Due to the historic nature of the weir, we had the sheet piles clad with brickwork using traditional materials and techniques to match the original weir feature (Figure 10) giving a very effective finish. The brickwork was completed by Herts Renovation, a locally based master stonemason.

During construction, despite a series of ground investigation boreholes and trial pits being sampled during the design phase, an unknown silt layer was discovered in the geology that was forming the left-hand bank of the new river and the right bank of the broadwater. Due to the permeable nature of this material, a bentonite lining was installed to create a water-tight boundary between the two water bodies.

Figure 10: Brick clad sheet piled section (January 2020) – Courtesy of Affinity Water

On the upstream half of the new river, a bifurcate channel has been constructed as well as an online pond feature and a wide shallow berm (Figures 11 and 12). Due to the location of the sewage pipe to the west of the new river, we were unable to create a meandering channel, so these features have been added to vary flow and create a diverse range of chalk stream habitats.

(left) Figure 11: Bifurcate section and (right) Figure 12: wide berm feature – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Completion

The new channel was made live in 2019 and features a series of natural pool and riffle sequences as should be seen in a chalk stream. The bed has been gravel-lined with site won gravel and low berms have been installed which will encourage the growth of marginal plants like watercress. The shallow fast flowing water with gravel bed will encourage the growth of chalk stream species like ranunculus and starwort. Deeper pool areas will provide good habitat for juvenile and adult fish while the in-channel and marginal vegetation will create refuge areas for small fry. Bypassing the Tumbling Bay Weir has meant that fish can now migrate upstream whereas before they would have been restricted by the height of the weir/barrier.

(left) Figures 13/14: Live bypass channel and Broadwater (December 2019) and (right) Figure 15: Aerial view of the new bypass channel and Broadwater (September 2019) – Courtesy of Affinity Water

Looking ahead

Ecological surveying is being carried out over the next 5 years to monitor the effectiveness of the project for chalk stream ecology. Results from the Phase 1 stretch, which has had longer to naturalise, has shown a range of chalk stream macroinvertebrates and the local Riverfly Group have recorded 80% of species expected in a chalk stream.