Tideway West – Hammersmith PS (2019)

Hammersmith Pumping Station - Courtesy of BMB JV

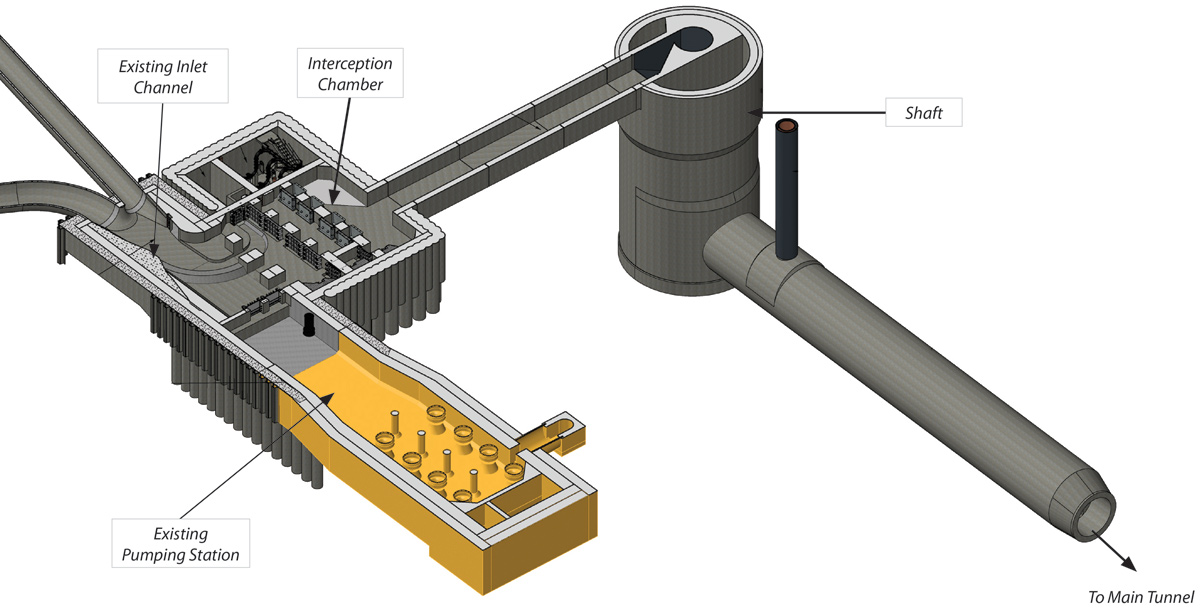

The Hammersmith Pumping Station is one of Thames Water’s key sewerage assets in West London. Its catchment covers an area of around 19 square miles, receiving flows from 47 combined sewer overflows (CSOs). The pumping station discharges 51 times in a typical year releasing 2,210,000m3 of untreated sewage and an estimated 557 tonnes of sewage derived litter into the River Thames. On completion of the Thames Tideway Tunnel and diversion of flows the annual discharge of untreated sewage will be reduced to 104,000m3, and the number of CSO discharges will be reduced to between one and three spill events per year. Sewage derived litter from the CSO can be expected to reduce by approximately 96% to approximately 26 tonnes in a typical year.

Existing pumping station

The pumping station dates from the late 1960s and is fed by two large inlet sewers (3.2m and 2.4m in diameter). The inlet channel is 15m deep, 30m long and 7.5m wide, and provides screening prior to the wet well where 8 (No.) storm pumps discharge flows to the river. The station receives flows of up to 25m3/s which can raise the levels in the channel by 8m in under ten minutes.

Flows will be diverted to the new tunnel, but the existing pumping station is to be retained for times when the tunnel is full or during tunnel maintenance.

Interception chamber

One of the biggest challenges faced by the BAM Nuttall, Morgan Sindall, Balfour Beatty Joint Venture (BMB) delivering the west section of the tunnel, was how the new Hammersmith interception chamber would be connected to the existing Hammersmith Pumping Station.

Doing so would involve extensive works in the inlet channel: removal of the screen cutwater, strengthening of the existing structure, the installation of a weir wall to the storm pump wet well and the formation of openings to the new interception chamber.

With no opportunity to divert or stop incoming flows, the inlet channel is a hostile environment and devising a safe system of work required extensive planning.

Cutwater removed and base slab strengthening in place – Courtesy of BMB JV

Sewer monitoring

16 of the 47 storm water overflow weirs within the sewer network were identified as being key to monitor flows arriving at Hammersmith. These overflows were fitted with ultrasonic and pressure sensors, which transmit in real-time the depth of flows within the foul sewers to Thames Water Utilities Limited‘s (TWUL) ICMLive, a vast computer model of their sewer system. The computer model combines the sewer layout and flow depth information with real time rainfall radar from the Met Office. The radar detects incoming storms, including their size and intensity and determines where the rain will land in the catchment.

Twice daily phone calls between the BMB site team, TWUL operational team, TWUL Waste Operations Control Centre (WOCC), and the ICMLive modelling team, ensured no surprise flows arrived. The model enables the team to determine when it is safe to work in the inlet channel and when flows will overtop the weirs. Not just relying on the computer model, the monitors will also sound an alarm at Hammersmith when they detect the weirs are overtopped.

The monitoring installation at Warwick Road had proven particularly troublesome. The team had to abandon sewer entry on three separate occasions, due to gas levels, heavy rainfall, and traffic issues. Access involved descending two separate levels within the sewer system, requiring two separate rescue teams. In addition, traffic management was particularly difficult due to access openings being situated in busy road networks; entry was only possible during the night.

Temporary works

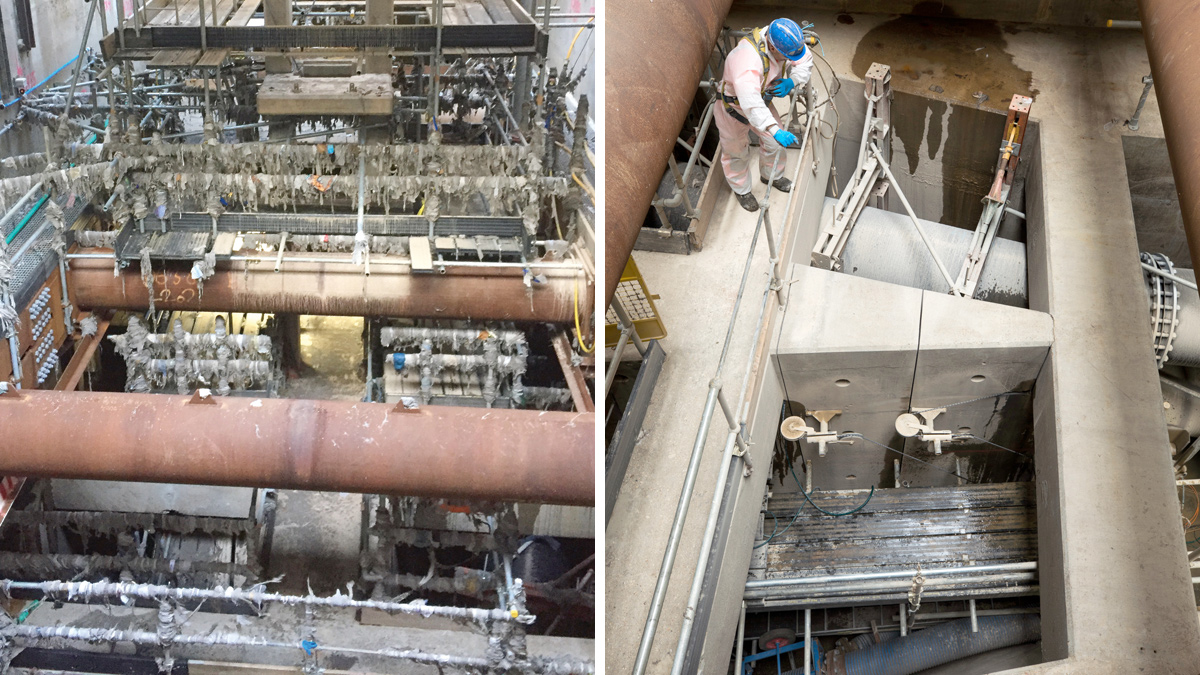

The inlet channel has a series of structural props at both roof level and mid-level that support the walls, transferring external soil loading across the structure. The construction of the adjacent interception chamber removes the soil to full depth on one side of the 15m deep inlet channel. This required extensive ground modelling in PLAXIS by Arup Atkins Joint Venture (AAJV), taking account of soil loading, heave and full depth water loading.

Using the modelling output AAJV and the BAM Nuttall temporary works team developed a construction sequence and propping scheme that used both temporary and permanent works to ensure that the structural integrity of the inlet channel was not compromised during construction.

Temporary props were installed within the inlet channel, between the existing roof and mid-level props. These would be subsequently matched by temporary props within the new interception chamber. Whilst this work was essential, it created further congestion in the inlet channel, complicating subsequent modifications.

Existing cutwall and intermediate level props – Courtesy of BMB JV

Within the inlet channel the existing single ladder access was replaced with a series of staircases and walkways to improve access. At the invert, the team installed two temporary weir walls, each 4.5m high and the full width of the inlet channel. Flows are conveyed through the weir walls by 2 (No.) 900mm flume pipes, creating a dry working area. Although the walls will be over-topped by larger storms, their significance is two-fold. Firstly, they allow works to continue during smaller storms, and secondly, and crucially they allow evacuation time for workers should the monitoring system fail. The temporary works were optimised by AAJV using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modelling and the following were assessed by the modelling:

- The impact of changes in the presentation of flows to the existing storm pumps and development of mitigation.

- Determination of the storm flow at which the temporary weir walls would be overtopped.

- Top water levels within the inlet channel to feed in to TWULs sewer model to ensure that no upstream flooding occurred.

Cutwater removal

(left) Inlet channel following storm event and (right) cutwater removal – Courtesy of BMB JV

Within the inlet channel there is an 18m long, 5m high, 2m wide mass concrete cutwater wall that supported two bar screens, which needed to be demolished. Various options were considered. Traditional excavators and breakers were rejected due to concerns on noise, dust, disturbance to residents, vibration, risks of stormwater inundation and the risk of broken concrete being washed into the TWUL storm pumps.

The method selected was to use diamond bedded rope concrete cutting. This created minimal dust and the equipment was easy to remove in the event of a predicted storm. Specialist concrete cutting firm John F Hunt worked closely with the BMB team and planned a network of vertical and horizontal cuts. The wall was divided into 130 (No.) concrete blocks, each up to 2.5 tonnes in weight. A hole was cored through each block to enable it to be lifted and lowered into a skip and lifted out using the site tower crane. It took of total of 13 weeks to complete the works, of which 15 days was lost due to either predicted heavy rain or removal of silt after a heavy flood event. Throughout the works there were no disruptions to the operation of Thames Water’s pumping station.

Base strengthening and low flow channel

Once the removal of the cutwater was completed, works were carried out to strengthen the inlet channel base slab, identified as being required by the PLAXIS modelling. This involved the provision of benching at the interface of the slab and walls and by adding reinforcement to the upper level of the base slab.

At the same time a low flow channel was cast, which will direct non-storm flows of up to 200 l/s to a new pumping station within the interception chamber. This is necessary to prevent premature discharges to the future tunnel.

Hammersmith Pumping Station (right) with inlet channel (foreground) – Courtesy of BMB JV

Further works

With the strengthening works complete the way is clear for the excavation of the adjacent interception chamber to full depth. Once this structure is completed, a weir wall will be formed across the start of the storm pump wet well and four openings will be made in the wall of the inlet channel to divert flows to the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

Conclusion

The works to the existing Hammersmith Pumping Station have required significant modifications to a 1960s structure, working in a dangerous environment. Devising and planning an intricate safe-system of work was borne from close collaboration between contractor BMB, designers AAJV and BAM Nuttall, Thames Water and Tideway. This was critical as each party held a piece of the puzzle.